EPA chief Jackson’s quest for environmental justice traces back to her New Orleans roots

By Dina Cappiello, APSaturday, January 9, 2010

Hurricane propels Jackson’s justice quest at EPA

NEW ORLEANS — More than four years after Hurricane Katrina, the single-story brick rancher in Pontchartrain Park where Lisa Perez Jackson grew up stands empty.

Floodwaters long ago ate away the walls of her corner bedroom, where the current head of the Environmental Protection Agency once hung Michael Jackson and Prince posters and studied her way to the top of her high school class.

Faded spray paint, left by search teams to indicate that no bodies were found, serves as a reminder of the day Jackson evacuated her mother, Marie, to Bossier City ahead of the approaching storm.

Katrina was the closest that an environmental disaster had hit home for someone who has spent her career solving environmental problems. Now, she’s in charge of ensuring that all communities are equally protected from pollution.

The storm’s toll on Jackson’s childhood house and on New Orleans, particularly the Ninth Ward where she was raised, has intensified her quest for what’s known as environmental justice. That means involving and getting fair treatment for the poor and minorities, who often endure the greatest exposure to environmental hazards but are outside the mainstream movement trying to find solutions.

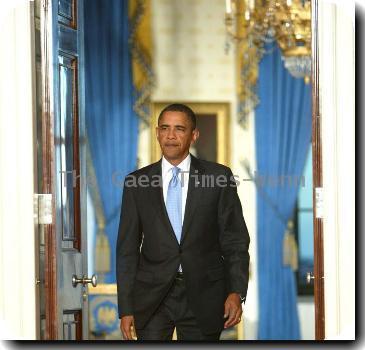

It’s this fight that Jackson wants most to be remembered for from her tenure as President Barack Obama’s chief environmental steward.

As the first black EPA administrator, Jackson has infused race and class into environmental decisions even though she acknowledges it’s not a top priority for Obama. She’s changed the way EPA does business with minorities and has called on the predominantly white environmental movement to diversify.

In speeches, she says she’s trying to alter the face of environmentalism. She started in her own office, appointing a special adviser for environmental justice issues and hiring a multiracial staff to lead an agency where she often finds herself the only nonwhite at the table.

“This is a unique moment, where you now have a person of color in charge of the EPA for the first time ever and not trying to make that into a one-liner, but say, ‘OK, what does that mean?’” said Jackson, 47, in an interview with The Associated Press.

“It means that I can sit in a room … and maybe use my position to hear in a different way folks who don’t feel heard. … It’s about me trying to figure out what I would like people to say about the Lisa Jackson EPA when I’m done. And I want them to say, ‘You know, she really opened that agency up, she really made ways that have lived past her for that agency to speak to people of color, to speak to the poor, and to make sure their issues are taken into account.’”

That philosophy was on full display during her first visit back to New Orleans as EPA head in November. Some community activists who felt shut out by the EPA during the Bush administration got a chance to meet with the agency leader for the first time.

When one group crashed an invitation-only luncheon with environmental justice leaders, Jackson told the organizers that she still wanted to hear what they had to say.

“I was shocked. When she said I am going to listen to you, I said, ‘Huh?’,” said Albertha Hasten, president of the Louisiana Environmental Justice Community Organizations Coalition, who said she was unaware the meeting required an invitation.

Jackson’s next stop was a sit-down with representatives of some of the nation’s largest environmental groups. Not only did the color of those around the table change, but so did the topic. Hasten and others discussed soil contamination, illegal dumping and health problems caused by industries in their communities. The big environmental groups talked to Jackson about the importance of saving the disappearing Gulf Coast.

“I feel both sides,” said Jackson in an interview after the two meetings.

Adopted at two weeks old from Philadelphia, Jackson and her two brothers were raised by Benjamin Perez, a postal delivery man in New Orleans’ French Quarter, and his wife, Marie, who sometimes worked as a secretary. Her father died when Jackson was in the 10th grade.

She grew up in the middle-class black suburb of Pontchartrain Park. The tight-knit neighborhood, centered around a golf course, resembled more of a Mayberry, the fictional Southern town from “The Andy Griffith Show,” than a pit of pollution amid industry, according to Troy Henry, a neighborhood resident and a candidate for mayor. It was home to politicians and professionals — and the actor Wendell Pierce.

“When I was growing up, it wasn’t like I looked around and said, ‘Well, I gotta do something about this, I live next door to a factory,’” said Jackson. “It is not that neighborhood.”

Her mother says she was “sheltered from some of the hurt that other people felt. She realized the differences and she knew that there were some people that didn’t have the same things she had. She always realized that neighborhoods were different, she realized as she got older … waterways and our pollution and our canals and the oil refineries and the drilling … (are) detrimental to people.”

After graduating from a girls’ only Catholic high school, Jackson made it to Tulane University, where she stood out in the chemical engineering department. She was one of the smartest, and the lone black woman in her class.

Sam Sullivan, emeritus associate dean of engineering who recruited Jackson to Tulane in the late 1970s, said, “She is a minority, her family was not rich. She grew up in that environment, so she can relate to some of the problems that people at that level have that frankly a lot of people who have been in that job just couldn’t do.”

Before Jackson took over at the EPA, Robert Bullard, regarded as the father of environmental justice, had “basically zero” contact with agency chiefs. He’s met with Jackson at least a dozen times.

“We never had anything like that before,” said Bullard, director of the Environmental Justice Center at Clark Atlanta University. “What that openness and access has to do with is that African-Americans and communities of color were shut out.”

Months after Katrina hit, Jackson was under consideration to be environmental chief for New Jersey Gov. Jon Corzine — a job she later took — and she couldn’t get back to New Orleans when her mother returned to Pontchartrain Park to clean up.

The house, like many in the neighborhood, was filled with 6 feet to 8 feet of water. There was no flood insurance to cover the damage, so Jackson’s mother eventually sold the home to the state.

Jackson hasn’t forgotten the photograph of her mother sent to her by the Catholic charity that helped gut her house. It shows Marie Perez in a wheelchair watching as all the belongings collected over her life were removed. She also can’t forget how she was unable to financially help her mother to rebuild.

During her visit to New Orleans in November, Jackson went back to Pontchartrain Park and learned that the house would be razed and rebuilt into an energy-efficient model.

“After the hurricane I kept saying if I were rich, I would knock this house down, and rebuild an energy-efficient, elevated house for my mother,” Jackson said. “But then to be able to come back as the head of the EPA and say maybe I couldn’t help my mother in her one instance, and thank God she is OK, but maybe I can help some people and help my city and help the Gulf Coast. You know even one or two times would make a difference.”

On the Net:

Lisa Jackson’s blog at EPA: blog.epa.gov/administrator/

Environmental Justice Resource Center, Clark Atlanta University: www.ejrc.cau.edu

Tags: African-americans, Barack Obama, Environmental Activism, Louisiana, Municipal Governments, New Orleans, North America, Storms, United States