Gulf Coast anxiously watches growing oil slick; worries of ‘nightmare’ scenario for Atlantic

By Seth Borenstein, APSunday, May 2, 2010

Gulf Coast dreads oil spill’s creep toward shores

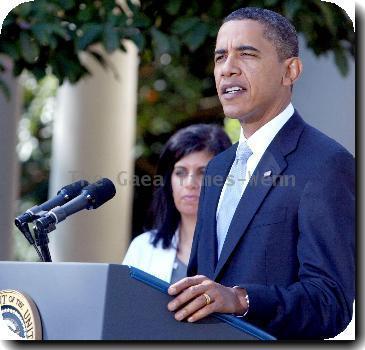

VENICE, La. — President Barack Obama headed to the Gulf Coast on Sunday for a firsthand update on a massive and growing oil slick creeping toward American shores from Louisiana to Florida.

Crews have had little success stemming the flow from the ruptured well on the sea floor off Louisiana or removing oil from the surface by skimming it, burning it or dispersing it with chemicals. Adding to the gloomy outlook were warnings from experts that an uncontrolled gusher could create a nightmare scenario if the Gulf Stream current carries it toward the Atlantic.

Long tendrils of oil sheen made their way into South Pass, a major channel through the salt marshes of Louisiana’s southeastern bootheel.

“That is the very first sign of oil I’ve heard of inside South Pass,” said Venice charter boat captain Bob Kenney, shaking his head. “It’s crushing, man, it’s crushing.”

South Pass is a breeding ground for the crab, oysters, shrimp, redfish and other seafood sold by his family’s wholesale and retail business in Slidell, Kenney said. The water was calm just after daybreak Sunday and long tendrils of the shiny slick stretched out toward the Gulf, even as mullet jumped out of the water near marsh grass that borders the pass.

There is growing criticism that the government and oil company BP PLC should have done more to stave off the disaster, which cast a pall over the region’s economy and fragile environment. Moving to blunt criticism that the Obama administration has been slow in reacting to the largest U.S. crude oil spill in decades, the White House dispatched two Cabinet members to make the rounds of the Sunday television talk shows.

“These people, we’ve been beaten down, disaster after disaster,” said Matt O’Brien of Venice, whose fledgling wholesale shrimp dock business is under threat from the spill.

“They’ve all got a long stare in their eye,” he said. “They come asking me what I think’s going to happen. I ain’t got no answers for them. I ain’t got no answers for my investors. I ain’t got no answers.”

He wasn’t alone. As the spill surged toward disastrous proportions, critical questions lingered: Who created the conditions that caused the gusher? Did BP and the government react robustly enough in its early days? And, most important, how can it be stopped before the damage gets worse?

The April 20 explosion of the Deepwater Horizon exploration rig killed 11 workers and the subsequent flow of oil threatens beaches, fragile marshes and marine mammals, along with fishing grounds that are among the world’s most productive.

The Coast Guard conceded Saturday that it’s nearly impossible to know how much oil has gushed since the blast, after saying earlier it was at least 1.6 million gallons — equivalent to about 2½ Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Even at that rate, the spill should eclipse the 1989 Exxon Valdez incident as the worst U.S. oil disaster in history in a matter of weeks. But a growing number of experts warned that the situation may already be much worse.

The oil slick over the water’s surface appeared to triple in size over the past two days, which could indicate an increase in the rate that oil is spewing from the well, according to one analysis of images collected from satellites and reviewed by the University of Miami. While it’s hard to judge the volume of oil by satellite because of depth, images do indicates growth, experts said.

“The spill and the spreading is getting so much faster and expanding much quicker than they estimated,” said Hans Graber, executive director of the university’s Center for Southeastern Tropical Advanced Remote Sensing. “Clearly, in the last couple of days, there was a big change in the size.”

Doug Suttles, BP’s chief operating officer for exploration and production, said it was impossible to know just how much oil was gushing from the well, but company and federal officials were preparing for the worst-case scenario.

In an exploration plan and environmental impact analysis filed with the federal government in February 2009, BP said it had the capability to handle a “worst-case scenario” at the site, which the document described as a leak of 162,000 barrels per day from an uncontrolled blowout — 6.8 million gallons each day.

Oil industry experts and officials are reluctant to describe what, exactly, a worst-case scenario would look like — but if the oil gets into the Gulf Stream and carries it to the beaches of Florida, it stands to be an environmental and economic disaster of epic proportions.

The well is at the end of one branch of the Gulf Stream, the warm-water current that flows from the Gulf of Mexico to the North Atlantic. Several experts said that if the oil enters the stream, it would flow around the southern tip of Florida and up the eastern seaboard.

“It will be on the East Coast of Florida in almost no time,” Graber said. “I don’t think we can prevent that. It’s more of a question of when rather than if.”

At the joint command center run by the government and BP near New Orleans, a Coast Guard spokesman maintained Saturday that the leakage remained around 5,000 barrels, or 200,000 gallons, per day.

But Coast Guard commandant Adm. Thad Allen, appointed Saturday by Obama to lead the government’s response, said no one could pinpoint how much oil is leaking because it is about a mile underwater.

“And, in fact, any exact estimation of what’s flowing out of those pipes down there is probably impossible at this time due to the depth of the water and our ability to try and assess that from remotely operated vehicles and video,” Allen said during a conference call.

Allen said a Friday test of new technology to reduce the amount of oil rising to the surface seemed to be successful. An underwater robot shot a chemical meant to break down the oil at the site of the leak rather than spraying it on the surface from boats or planes, where the compound can miss the oil slick.

From land, the scope of the crisis was difficult to see. As of Saturday afternoon, only a light sheen of oil had washed ashore in some places.

The real threat lurked offshore in a swelling, churning slick of dense, rust-colored oil the size of Puerto Rico. From the endless salt marshes of Louisiana to the white-sand beaches of Florida, there is uncertainty and frustration over how the crisis got to this point and what will unfold in the coming days, weeks and months.

The concerns are both environmental and economic. The fishing industry is worried that marine life will die — and that no one will want to buy products from contaminated water anyway. Tourism officials are worried that vacationers won’t want to visit oil-tainted beaches. And environmentalists are worried about how the oil will affect the countless birds, coral and mammals in and near the Gulf.

“We know they are out there” said Meghan Calhoun, a spokeswoman from the Audubon Aquarium of the Americas in New Orleans. “Unfortunately the weather has been too bad for the Coast Guard and NOAA to get out there and look for animals for us.”

Fishermen and boaters want to help. But on Saturday, they were again hampered by high winds and rough waves that splashed over the miles of orange and yellow inflatable booms strung along the coast, rendering them largely ineffective. Some coastal Louisiana residents complained that BP, which owns the rig, was hampering mitigation efforts.

“I don’t know what they are waiting on,” said 57-year-old Raymond Schmitt, in Venice preparing his boat to take a French television crew on a tour. He didn’t think conditions were dangerous. “No, I’m not happy with the protection, but I’m sure the oil company is saving money.”

As bad as the oil spill looks on the surface, it may be only half the problem, said University of California Berkeley engineering professor Robert Bea, who serves on a National Academy of Engineering panel on oil pipeline safety.

“There’s an equal amount that could be subsurface too,” said Bea. And that oil below the surface “is damn near impossible to track.”

Louisiana State University professor Ed Overton, who heads a federal chemical hazard assessment team for oil spills, worries about a total collapse of the pipe inserted into the well. If that happens, there would be no warning and the resulting gusher could be even more devastating because regulating flow would then be impossible.

“When these things go, they go KABOOM,” he said. “If this thing does collapse, we’ve got a big, big blow.”

BP has not said how much oil is beneath the seabed Deepwater Horizon was tapping. A company official speaking on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to discuss the volume of reserves, confirmed reports that it was tens of millions of barrels — a frightening prospect to many.

Obama has halted any new offshore drilling projects unless rigs have new safeguards to prevent another disaster.

As if to cut off mounting criticism, on Saturday White House spokesman Robert Gibbs posted a blog entitled “The Response to the Oil Spill,” laying out the administration’s day-by-day response since the explosion, using words like “immediately” and “quickly,” and emphasizing that Obama “early on” directed responding agencies to devote every resource to the incident and determining its cause.

The White House also scheduled Interior Secretary Ken Salazar and Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano on Sunday morning talk shows to detail the administration’s efforts. Joining them was the commandant of the Coast Guard, Adm. Thad Allen.

In Pass Christian, Miss., 61-year-old Jimmy Rowell, a third-generation shrimp and oyster fisherman, worked on his boat at the harbor and stared out at the choppy waters.

“It’s over for us. If this oil comes ashore, it’s just over for us,” Rowell said angrily, rubbing his forehead. “Nobody wants no oily shrimp.”

Borenstein reported from Washington; Associated Press writers Tamara Lush, Brian Skoloff, Melissa Nelson, Mary Foster, Michael Kunzelman, Chris Kahn, Vicki Smith, Janet McConnaughey, Alan Sayre and AP Photographer Dave Martin contributed to this report.

Tags: Accidents, Animals, Arts And Entertainment, Barack Obama, Coastlines And Beaches, District Of Columbia, Energy, Environmental Concerns, Executive Branch, Florida, Gulf, Louisiana, Mammals, Military Technology, New Orleans, North America, Television Programs, Tv News, United States, Venice