After initial uncertainty, Obama’s response to Haiti earthquake disaster gained quick momentum

By Robert Burns, APSaturday, January 16, 2010

Slow start, then Obama gained momentum on Haiti

WASHINGTON — Hillary Rodham Clinton was in a Honolulu hotel lobby and getting ready to fly to the South Pacific when she finished a series of cell phone calls to Washington. The trip was still on, the secretary of state told reporters, despite the terrible earthquake in Haiti almost a day earlier.

A few hours later she was hightailing it back to Washington.

The sudden change epitomized the initial uncertainty, in the White House and elsewhere in government, about the scale of the disaster, the challenge of mounting a sufficient response and the risk that the administration would be seen as not taking it seriously enough.

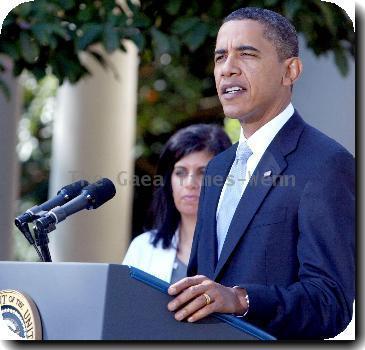

President Barack Obama responded with urgency and the White House made sure people knew it.

But in those initial hours after the quake hit, shortly before 5 p.m. Tuesday, no one knew just how bad it was. “Biblical,” Clinton said of the devastation in Haiti, where she had honeymooned 34 years ago.

Communications were so thoroughly severed that Obama had trouble reaching President Rene Preval. Death and damage assessments were hard to come by.

“We do not have the kind of information yet that gives us a road map as to how we’re going to be able to respond effectively,” Clinton told reporters in Hawaii at 1 p.m. EST Wednesday. She spent about the next four hours down the road at U.S. Pacific Command headquarters and emerged to say she would return immediately to Washington.

Although a response plan was still in the making, the military wasted no time preparing for what its leaders expected to become a taxing mission of disaster relief, search-and-rescue and possibly street security.

Lt. Gen. Philip Breedlove, the Air Force’s deputy chief of staff for operations, got a midnight phone call Tuesday in Washington. It was his job to start pulling together air transportation and logistics experts.

By sheer coincidence, a senior Army general based in Miami happened to be in Haiti when the quake struck. Lt. Gen. Ken Keen, a deputy chief of U.S. Southern Command, instantly became the chief architect of the military’s response plan. He would coordinate operations from the broken airfield at Port-au-Prince, the capital.

At the White House in the first hours after the 7.0-magnitude quake, Obama was twice briefed on the situation. At 10 p.m. Tuesday, his deputy national security adviser, Tom Donilon, convened a Situation Room session with national security and military officials.

That evening, the White House released a statement from the president in which he expressed sympathy for the victims and said his government stood ready to assist. The White House said Obama was told about the quake at 5:52 p.m. EST Tuesday, about an hour after it struck, while conducting an Oval Office meeting on health care legislation. In his written statement, he emphasized the need to ensure that U.S. Embassy personnel were safe and to begin preparations to help Haiti.

As of Saturday, one embassy staffer was confirmed dead; three other U.S. government officials were missing. The State Department said the total number of confirmed U.S. deaths stood at 15.

It was clear from the outset that the Obama White House was determined that this should not be a repeat of the Bush administration’s response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005. George W. Bush paid a huge political price when people saw New Orleans drowning and governments at all levels were slow to respond.

The Haiti quake is different, of course, not least because it happened hundreds of miles from U.S. shores. But this administration nevertheless was quick to talk up the need to help.

At about 2 p.m. Tuesday in Honolulu (7 p.m. in Washington), before Obama made his first public remarks on the quake, Clinton mentioned it at the start of a speech focused on Asian affairs. She said the U.S. was gathering information on the scale of the disaster but was pledging “full assistance” to Haiti.

Coast Guard cutters and aircraft were moved closer to Haiti.

At first light Wednesday, a Coast Guard helicopter evacuated four seriously injured U.S. Embassy workers to the U.S. Navy base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Although the Haitians took the heaviest blows, Washington had to worry about the 45,000 American citizens there, including the embassy contingent.

At 10 a.m. Wednesday, speaking publicly about the quake for the first time, Obama said the U.S. government was “just now beginning to learn the extent of the devastation.” Help was on the way, he said, adding that he had put Rajiv Shah, chief of the U.S. Agency for International Development, in charge of coordinating the U.S. response and working with other nations.

Shah, a medical doctor and food security expert, had started his job at USAID just five days before the quake, taking over an agency with reduced resources and influence, a leadership vacuum and weakened morale.

At about 1 p.m. Wednesday, just before Clinton was to board a plane in Honolulu and fly through another 10 time zones to the South Pacific island of Papua New Guinea — and after that to New Zealand and Australia — Obama spoke to her at her hotel as her motorcade idled under a sunny sky.

Hotel guests gawked at the former first lady in sunglasses as she stood in a corner of the lobby to speak on her cell phone and confer quietly with aides. She then told reporters traveling with her that the trip would go on, although perhaps with a condensed itinerary.

“These are also very important travel destinations for a lot of America interests,” she said. “And speaking with the president, he and I agreed that I should go on with the trip.” She added: “We feel an obligation” to continue.

At that point there were not yet official estimates of the death toll in Haiti. After she announced at 1 p.m. (6 p.m. EST) that she would return to Washington, Clinton said one reason was that unofficial estimates of 100,000 dead might turn out to be way low.

In the following hours, as she flew home, Obama held Situation Room meetings with senior civilian and military aides who were coordinating the relief effort. Obama directed them to “work with and through” the crippled Haitian government “to the greatest extent possible,” according to a senior administration official who described the session on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to discuss private meetings.

At about the same time, Defense Secretary Robert Gates used a videoconference with leaders at U.S. Southern Command to insist there was “no higher priority right now” than the relief effort.

By Thursday the full scope of the U.S. effort was beginning to come into focus: Obama pledged an initial $100 million in aid; the first group of U.S. search and rescue teams were on the ground; a survey team had identified priorities areas for assistance; the airport at Port-au-Prince was ready for limited use to deliver food and water; elements of the 82nd Airborne Division were about to arrive; and the aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson and the hospital ship USNS Comfort were designated to head to Haiti.

By Saturday, Clinton had made her way to Haiti for a first look at how the relief effort was unfolding. Obama was again in front of the TV cameras at the White House, promoting “one of the largest relief efforts in our history” while trying to hold down expectations for quick success.

Associated Press writers Anne Flaherty, Darlene Superville, Jennifer Loven and Julie Pace contributed to this report.

Tags: Barack Obama, Caribbean, District Of Columbia, Embassies, Emergency Management, Haiti, Hawaii, Honolulu, Latin America And Caribbean, North America, Personnel, Port-au-prince, Search And Rescue Efforts, United States, Washington