War-crimes trial of youngest Gitmo detainee opens with tape showing him making bombs

By Mike Melia, APThursday, August 12, 2010

War-crimes trial opens for youngest Gitmo inmate

GUANTANAMO BAY NAVAL BASE, Cuba — A war-crimes trial for Guantanamo’s youngest detainee opened Thursday with prosecutors showing an al-Qaida video of him making — and apparently planting — bombs in Afghanistan.

Prosecutors and defense lawyers offered competing views of whether Omar Khadr, who was 15 when he was captured in 2002, was capable of acting independently from the Islamic extremist father who took him to Afghanistan.

In the video found in an al-Qaida compound, Khadr showed only the faint beginnings of a mustache. Now a broad-shouldered, full-bearded man of 23, he sat before a military jury charged with crimes including spying, supporting terrorism and murder for allegedly throwing a grenade that killed a U.S. Special Forces soldier. Khadr has pleaded not guilty to all charges.

Prosecutor Jeff Groharing accused Khadr of embracing terrorist ideology as his own and describing operations against U.S. forces with pride even after his capture.

“‘I am a terrorist trained by al-Qaida.’ Those are Omar Khadr’s own words,” Groharing said, describing one of the detainee’s first interrogations at Guantanamo. “Omar Khadr decided to conspire with al-Qaida so he could kill as many Americans as possible.”

But a Pentagon-appointed defense lawyer said Khadr was a victim himself, pushed into war as an impressionable child by his father, alleged al-Qaida financier Ahmed Said Khadr.

“He was there because his father told him to go there,” Army Lt. Col. Jon Jackson said. “He was there because Ahmed Khadr hated his enemies more than he loved his son.”

The first day of testimony adjourned early after Jackson collapsed while questioning a witness. He was hospitalized and receiving morphine for a complication related to gall bladder surgery he underwent six weeks ago, said Bryan Broyles, the tribunals’ deputy chief defense counsel.

Broyles said it was unclear whether Jackson, the only attorney authorized to represent Khadr, would require surgery or whether he might need to be flown to the United States for treatment.

The case has been delayed for years by legal wrangling and a series of challenges to the system of war-crimes trials, known as military commissions, that was set up during the Bush administration and has been criticized by human rights groups for not including the same protections as federal courts or traditional courts-martial.

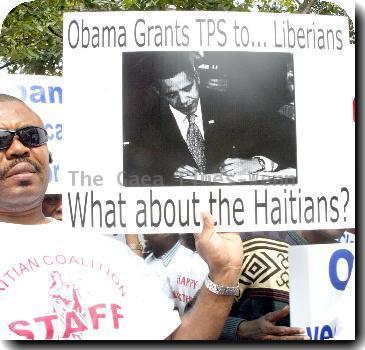

The Khadr trial is now the first under the administration of President Barack Obama, who revised the system to offer more protections to defendants and is considering it as a venue for the prosecution of more prominent suspects such as alleged 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.

The video introduced as one of the first pieces of evidence was recovered along with bomb-making materials from a mud-walled compound in eastern Afghanistan where Khadr allegedly threw the grenade that killed Sgt. 1st Class Christopher Speer, 28, of Albuquerque, New Mexico.

A firefight lasting roughly four hours broke out July 27, 2002, between men holed up inside the compound and a team of U.S. forces, Afghan soldiers and at least one CIA operative. Fighter jets blasted the site with rockets and two 500-pound bombs. As the smoke cleared and a Delta Force team entered the compound, a grenade exploded at the feet of Speer, who died from his injuries days later.

His widow, Tabitha Speer, watched the proceedings inside the courtroom but was not expected to testify until a possible sentencing hearing.

Khadr has denied throwing the grenade. Jackson, the defense lawyer, said another fighter lobbed the explosive before he was killed by a U.S. soldier who also shot Khadr twice in the back.

The commanding officer at the battle, identified only as “Col. W” because of security reasons, testified Khadr appeared to have such a small chance of surviving his wounds that he wrote in a report hours later that the grenade thrower had died. The officer, a National Guardsman who is a police officer in civilian life, revised the report some two years later after he was contacted by prosecutors preparing a case against Khadr.

No eyewitness saw Khadr throw the grenade, and defense lawyers say the case depends on purported confessions extracted through mistreatment, including one interrogation conducted while he was still on a stretcher in Bagram, Afghanistan.

Jackson said Khadr only made a confession after his first interrogator told him a story about an uncooperative Afghan youth who was sent to an American prison and raped.

The jury of seven military officers — four men and three women — was seated Wednesday from a pool of 15. Prosecutors lost an argument to dismiss a U.S. Navy captain who said he believes Guantanamo is a “kinder, gentler” place than when Khadr was brought here in 2002, and used their only automatic dismissal to eliminate a potential juror who said Guantanamo should be closed.

Khadr’s youth has made his case one of the most followed by critics of Guantanamo. Child advocates have argued Khadr should face rehabilitation rather than a possible life sentence, and say prosecuting a minor for war crimes could set a dangerous international precedent and lead to more youths being victimized by war.

Where other Western countries have successfully lobbied for the return of their nationals from Guantanamo, Canada has repeatedly refused to intervene despite pressure from opposition parties and a recent Canadian Supreme Court ruling that ordered it to protect Khadr’s rights.

The reluctance owes partly to Canadians’ ambivalence to the Khadr family, which has been called “the first family of terrorism.

The defendant’s father, Ahmed Said Khadr, was an Egyptian-born Canadian citizen killed in 2003 when a Pakistani military helicopter attacked the house where he was staying with senior al-Qaida operatives. A brother, Abdullah Khadr, is wanted in the United States for allegedly purchasing weapons for al-Qaida and plotting to kill Americans abroad.

Omar Khadr’s trial at this U.S. Navy base in southeast Cuba is expected to last three to four weeks.

Tags: Afghanistan, Asia, Barack Obama, Bombings, Canada, Caribbean, Central Asia, Cuba, Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, Latin America And Caribbean, Military Legal Affairs, North America, Terrorism, United States