Pakistan’s flood victims return home to find their old lives and possessions have disappeared

By Tim Sullivan, APThursday, August 26, 2010

Pakistani flood victims return home to destruction

AZAKHEL, Pakistan — This is what Anar Gul found when he came home: Eight thin mattresses covered with polyester swirls; a dozen blankets; a broken tape player; and a large metal box buried deep in the mud. The clothes inside had begun to rot after more than two weeks in the ground.

After more than 30 years of carving out the semblance of a working-class life, this junk spread out to dry on the wreckage of his house was now all Gul had.

“This is everything,” he said, waving his hands at the muck and the garbage.

Nearly a month after floods first began battering Pakistan, and as waters still sweep through the south, the first victims are coming home. Millions of people may soon find that, like Gul, their old lives have disappeared — and that the receding water is only the start.

“There are so many houses to be rebuilt. It’s not only here, it’s everywhere,” said Gul, a gentle man with a gray beard turning yellow with age, who thinks he’s about 70 years old. He supported his sprawling family as a middleman, arranging deals between farmers and wholesalers in the local fruit market. It was a good life, and the former wood cutter had built a mud-walled house with three bedrooms, a guest room, a bathroom and a courtyard. They had ceiling fans and a sewing machine.

Now, though, the house is obliterated, the fruit business has been hobbled by the floods, and his nine-member family is jammed into a single U.N.-supplied tent. Every day, he sends his 10-year-old son, Hamid, to dig through the mud around his old house in search of anything more.

“We understand the devastation is so intense that even the government cannot help everyone,” Gul said as the smell of rotting food and dead animals filled the air, and mobs of flies clustered on stains on his baggy pants. “But the government needs to help us.”

The floods began here, in northwestern Pakistan, in late July when the annual monsoon rains began falling. Azakhel, a small town outside the city of Nowshera, saw thousands of houses completely submerged. Most people had fled by the end of July and only came back in the last week or so.

Rivers swollen by rain that fell in the mountainous north have flowed southward, ravaging a massive swath of the country’s agricultural heartland. Only in the coming days are floodwaters expected to begin fully draining into the Arabian Sea.

More than 1,500 people died, most in flash floods in the initial days. The death toll does not reflect the scale of the crisis, however, with millions of acres under water and the vital agricultural economy devastated.

More than 8 million people need emergency assistance, and the international community has pledged hundreds of millions of dollars in aid.

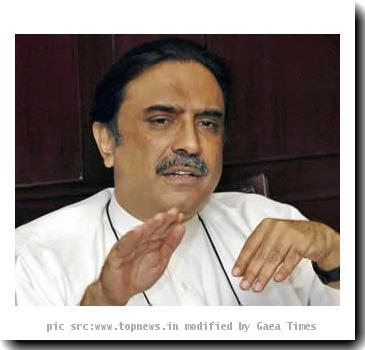

Rahimullah Yousafzai, a prominent Pakistani writer, said the promises of international aid could backfire. The pledges “are actually creating expectations, which are very high. … But knowing my country and the government and the politicians, I don’t expect there will be fair distribution of resources.”

It’s not clear yet what help people will get. The government of President Asif Ali Zardari has promised 20,000 rupees ($230) to families affected by the floods, with a presidential spokesman calling the payment “initial assistance.”

Most Pakistanis are also distrustful of their government. Zardari is still commonly referred to as “Mr. Ten Percent” because of unproven allegations that he pocketed millions of dollars in commissions on government contracts when his wife, Benazir Bhutto, ruled the country.

“People have lost all their belongings and their cattle and their crops,” said Yousafzai, who says squabbling over aid could lead to ethnic and regional tensions and possibly anti-government unrest. “The president is saying ‘We’re going to build a new Pakistan.’ It’s not realistic. They can’t do it.”

It’s clear that frustration is building as people return home. Government officials, for the most part, are nowhere to be seen. Of the official aid that has arrived, people here say most has been given to supporters of local political bosses.

“The government hasn’t even bothered to ask if we are living or dying,” said Karim Baksh, a retired bureaucrat with the state electricity company.

His home in Nowshera was all but leveled by floodwaters. “I was the owner of such a large house — I was a landlord! — and now I’m living with my entire family in a tent,” Baksh said.

The only help he and his neighbors have received so far has come from aid organizations or private donors.

One of those neighbors, 23-year-old business student Yasir Naseer, urged international aid groups to distribute help on their own.

“People here are poor, and they know now how much help they need,” he said. “But don’t give any cash or anything to our government officials. They cannot be trusted.”

Tags: Asia, Asif Ali Zardari, Azakhel, Emergency Management, Floods, Foreign Aid, Pakistan, South Asia