Sinking of Russian submarine taught Putin value of controlling TV, projecting his authority

By Lynn Berry, APThursday, August 12, 2010

Sinking of Russian submarine taught Putin a lesson

MOSCOW — The sinking of a nuclear submarine 10 years ago taught Vladimir Putin a lesson that shaped his leadership of Russia: When disaster strikes, take control — most importantly of television.

After critical coverage of the Kursk sinking early in his presidency, Putin put all national channels under government control and began using footage of himself personally managing crises in a way that convinces many Russians he is the only person they can count on to keep them safe.

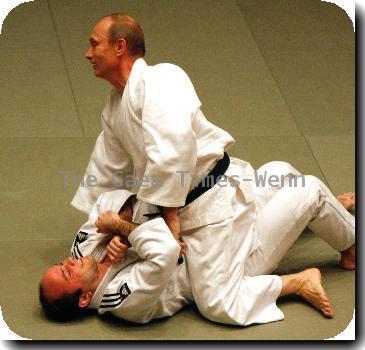

During his eight years as president and during the past two as prime minister, Putin has learned to use television to cultivate the image of a macho leader much loved by the Russian people. He has been shown piloting fighter jets, riding a horse bare-chested through rugged mountains and petting Siberian tigers. Wherever he goes, he is met by adoring crowds and obsequious officials.

His mastery of television has been on full display in recent weeks as he has taken command of efforts to extinguish the wildfires now sweeping across much of western Russia and to help the thousands of people who have lost their homes.

Wearing jeans and button-down shirts, Putin has traveled to villages scorched by the wildfires, where he has consoled weeping women and promised that their houses would be rebuilt before winter. Earlier this week, he climbed into a firefighting plane and from the copilot’s seat dumped tons of water onto burning forests. He also has threatened to oust local leaders who don’t do enough to fight the fires or help their constituents.

President Dmitry Medvedev, his junior partner in running Russia, has mainly been shown meeting with officials and also taking phone calls from Putin as he oversees the firefighting operation.

During Putin’s first visit to a fire zone, television showed him calling Medvedev on a cell phone and then switched to footage of the president taking the call in his office and promising to mobilize the army.

The unstated message is that Putin is the one who can be counted on to protect Russia and its people.

The situation was far different when two powerful explosions sank the Kursk, one of Russia’s most advanced submarines, during naval maneuvers in the Barents Sea on Aug. 12, 2000. An explosive propellant that leaked from a faulty torpedo had set off the blasts.

Most of the 118 members of the crew were killed instantly, but as the submarine sank to the bottom of the sea, only about 350 feet (108 meters) below the surface, 23 men were able to flee to a rear compartment, where they waited for help.

It was the first real test of Putin’s three-month-old presidency and he bungled it.

When the submarine sank, Putin was vacationing with his family in Sochi on the Black Sea. He did not interrupt his vacation, and his most memorable action during the early days of the crisis was to take a spin on a personal watercraft.

The bewildered navy command hesitated for hours before launching a search, wasting what little time was left for the trapped sailors. The government then turned down offers of Western assistance and stubbornly sent Russian mini-submarines to make repeated futile attempts to hook onto the submarine’s escape hatch.

Russia finally invited Norwegian divers and it took them only hours to open the hatch that the Russian submersibles had struggled with for an entire week. Putin returned to the Kremlin only when it was clear that none of the crew had survived.

Throughout the crisis, naval officials issued a string of contradictory information about what sank the Kursk and the fate of the crew, much of it soon revealed to be simply untrue.

Two national television networks owned by oligarchs Vladimir Gusinsky and Boris Berezovsky took the government to task for its failure to rescue the sailors and exposed the lies. The critical reports did much to fuel public anger.

Among the most extraordinary television footage at the time was from an Aug. 23 meeting between officials and relatives of the dead crew. When the distraught mother of one young sailor began to shout at the officials, a medic approached her from behind and injected her with a sedative, and she was carried from the room. All of Russia watched as a grieving woman who had dared to criticize the government was silenced.

Putin was livid. Within a year, both oligarchs were living in exile and their television stations were under government control.

“Kursk was a strong disappointment for Putin,” said Alexander Golts, a military and political analyst. “He faced shameless and insolent lies (from the military), and was very irritated by the media showing his powerlessness.

“He made a number of conclusions — first, that the mass media should be put in order, especially television.”

The takeover of Gusinsky’s NTV and especially of Berezovsky’s ORT caused relatively little public outcry.

“It turned out that people were tired of shocking investigations and did not want to find out what really happened to the Kursk,” political commentator Sergei Shelin wrote in a piece posted on Gazeta.ru. “People wanted only the good and merry news that the authorities have been spoon-feeding them ever since.

“It was then when Vladimir Putin and his circle finally realized that the country loves only those loved by national television,” Shelin wrote. “And it will dislike those disliked by television.”

Some sociologists have warned that anger over the raging fires threatens to erode public support for the president and prime minister, but government control over television and Putin’s skill at using the medium to maximum effect make this less likely. Some even suggest Putin’s popularity may grow.

On television, he no longer resembles the man who appeared on CNN’s “Larry King Live” program a few weeks after the Kursk tragedy. King asked him what happened with the submarine.

“It sank,” was Putin’s chilly answer.

_____

Associated Press writer Mansur Mirovalev contributed to this report.

Tags: Eastern Europe, Emergency Management, Europe, Moscow, Russia, Vladimir Putin