Two big jobs: Spill recovery chief to split time as Navy boss, puzzling some environmentalists

By Matt Apuzzo, APFriday, June 18, 2010

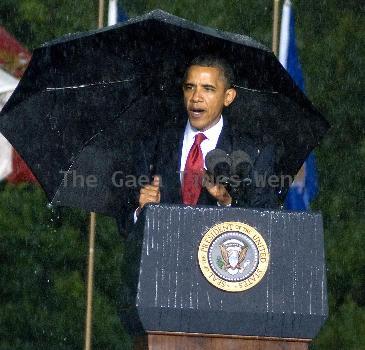

Obama’s spill recovery chief will be part-time

JACKSON, Miss. — Gulf Coast environmentalists and business owners are skeptical of President Barack Obama’s plan to have his point man for recovery perform his job part-time. And they’re worried the cleanup will become mired in bureaucratic deliberations.

Obama tapped Navy Secretary and former Mississippi Gov. Ray Mabus this week for an amorphous second job leading the environmental and economic recovery. His job is no less than rebuilding a region that was still suffering from Hurricane Katrina and beset by decades of environmental problems even before the largest oil spill in U.S. history.

Unlike President George W. Bush’s pick to lead Katrina’s recovery, Mabus is not stepping down from his day job, in which he oversees 900,000 Navy and Marine personnel.

“The president is confident that Governor Mabus is going to be able to provide the leadership that’s necessary to do both these jobs,” White House spokesman Bill Burton said Friday.

Others felt differently, adding to their criticism that Obama has not responded quickly or forcefully enough to the spill.

“The idea that he is only going to work on this part-time is disturbing,” said Robert Irvin, Defenders of Wildlife’s vice president for conservation programs. “If this is the equivalent of war, as the president has been saying, it needs a full-time general.”

In Ocean Springs, Miss., where oil-absorbing underwater fencing has been installed to protect marshlands, waterfront restaurateur Mickey McElroy said Friday the recovery job is too much for a part-timer.

“I’m just a little peon down here, and some of my people work two jobs. And if their first job is during the day and they come see me at night, I don’t get their best,” said McElroy, whose business relies on clean shrimp, redfish and oysters from the Gulf.

In his year at the helm of the Navy, Mabus has called for a cleaner, more energy-efficient fleet. But he remains largely an unknown to environmental groups helping clean up nation’s worst environmental disaster with oil still gushing from the offshore BP well after nearly two months.

“I don’t know what demands being head of the Navy requires, but from what I’ve heard he’s got a good head on his shoulders,” said Jill Mastrototaro, the head of the Sierra Club for the gulf region.

Kerry St. Pe, who said he oversaw hundreds of oil spills as a cleanup official with Louisiana’s environmental agency, said Mabus will need to appoint people to help him because “one person cannot do that job, and certainly not part-time.”

Environmentalists fear Mabus’ job will mean more deliberations in a region where environmental problems have been studied and discussed for years. There is no shortage of plans,” said Greenpeace research director Kert Davies. “You wonder when the plan becomes active.”

“Human beings, we love to plan, and so we do it, repeatedly,” said St. Pe, the director for the Barataria Terrebonne National Estuary Program. “We plan, and then we plan the plan, and then we make another plan. Somewhere along the line we’ve lost the implementation gene. You decide on a plan and then you implement it.”

While Obama selected Mabus for his ties to the Gulf Coast, the wealthy businessman also has had financial ties to the oil industry. Environmentalists want to know more about that.

When Mabus joined the Obama administration, energy investments were among the largest holdings in his portfolio. Between $350,000 and $750,000 was invested in partnerships that trade energy commodities such as crude oil and natural gas. He also owned between $15,000 and $51,000 in ExxonMobil stock and as much as $69,000 in energy mutual funds.

Mabus, whose net worth is in the millions, sold all his energy holdings upon taking office, Navy spokesman Thomas Oppel said.

The White House has not said exactly what Mabus’ job will be, so it’s unclear what sway he will have over the future of Gulf Coast environmental regulations and economic development policies, two things that could affect the coastal oil industry.

“Nothing in his background would suggest he will do anything but put the interests of the people of the Gulf first as he completes this critical mission, and the president has full confidence in his leadership,” White House spokesman Ben LaBolt said.

Mabus was one of the Democratic Party’s rising stars when he was elected Mississippi governor in 1987. He had exposed county government corruption as state auditor and campaigned for governor with the slogan “Mississippi will never be last again.”

But Mabus had a strained relationship with lawmakers. In a state where legislators, not the governor, have the most power, he saw many of his proposals snubbed. At his urging, lawmakers expanded Medicaid coverage, but other efforts such as spending more money on early childhood literacy never materialized.

In his new job, Mabus must build consensus across the region. Already there are signs that won’t be easy. Louisiana’s former Republican Gov. Buddy Roemer declared that Obama “could not have picked a better man,” but Mississippi’s governor, Haley Barbour, was quick with a barb.

“If this is really what it sounded like — that is, the federal government is going to make a long-term plan for the Gulf states — then it’s a terrible idea,” Barbour, a possible Republican candidate for president in 2012, told The Associated Press in a phone interview. “Mississippians will decide about Mississippi’s future.”

In his only major environmental decision as governor, Mabus angered politically powerful farmers in 1989 by opposing a plan to build the world’s largest pumps to drain water from flood-prone areas in the Yazoo River basin in rural western Mississippi. Mabus said the proposed federal project would have damaged sensitive wetlands to help agricultural interests.

The project was discussed for decades, and the EPA eventually vetoed the $220 million proposal in 2008.

Mabus’ decision to allow dockside casino gambling along the Mississippi River and Gulf Coast became his unexpected legacy. Millions of dollars poured into Mississippi’s budget, but in a state with historically weak environmental regulations, the decision allowed widespread development in sensitive coastal areas.

Mabus angered many of his own supporters — including, critically, the Legislative Black Caucus — by closing Mississippi’s three charity hospitals, which for decades had cared for some of the poorest people in the nation. He never recovered politically and lost the 1991 governor’s race to Republican Kirk Fordice, a blunt-spoken contractor.

During the re-election campaign, Mabus received $1,000 each from oil companies BPAmerica, Shell and Chevron. Each gave the most allowed by law, a tiny fraction of a $3 million campaign that got much broader support from bankers and lawyers.

An early supporter of Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton’s presidential bid, Mabus landed in the Clinton administration as ambassador to Saudi Arabia. He was the top U.S. diplomat to the oil-rich nation from 1994 until shortly before the deadly Khobar Towers terrorist attacks in 1996.

After helping with Clinton’s re-election campaign, Mabus stepped out of politics. But he was cast into the public eye in 1998 because of a messy divorce. The divorce became national news because Mabus secretly recorded his wife’s conversation with a priest, catching her admitting adultery.

Mabus owns more than 4,700 acres of Mississippi timberland worth between $5 million and $25 million. As CEO of Foamex International Inc. from 2006 to 2007, he steered the polyurethane foam products company out of bankruptcy.

He was an early supporter of Obama’s presidential campaign, endorsing him in 2007 and surprising some political observers who had expected him to support Hillary Rodham Clinton because of his past political ties to Bill Clinton.

Political savvy may be the most important aspect of Mabus’ new job. Steven Peyronnin, executive director of the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana, said Mabus can learn quickly about environmental problems. What the coast needs, Peyronnin said, is someone who can make decisions and get things done quickly.

Matt Apuzzo reported from Washington.

Tags: Accidents, Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, Campaigns, Coastlines And Beaches, District Of Columbia, Emergency Management, Environmental Activism, Environmental Concerns, Environmental Laws And Regulations, Government Regulations, Jackson, Louisiana, Middle East, Mississippi, North America, Personal Finance, Personal Investing, Political Fundraising, Saudi Arabia, United States, Washington